-The plastic foldable chairs have very soft, bendy back supports and you can't really lean into them. You have to sort of hover, exerting only gentle pressure.

-I'm suburnt from walking the length of Manhattan yesterday. One side of my face is pink, verging on red. I feel like people are looking at me going, 'Who let that pink guy in here?'

-There are three introductions to the talk.

-Also, we thought it would be nice to walk over Williamsburg Bridge to get here, but now I am sweaty and the room is warm and I'm not cooling down.

-Negarestani is wearing a lapel mic but it must be hidden behind his collar because it sounds like he is underwater.

-There's a heavyset middle aged guy in front of me with slicked back hair and what for some reason I'm thinking of as a "sports jacket" even though I don't know what that is. He leans hard back in his bendy chair and puts his arm round the back of the chair next to him.

-Negarestani says, 'What it means to take something as true and what it means to make something true.'

-Negarestani says something about philosophy driving a wedge between mind and the world, but I'm not sure if he is talking historically, and if so, when was the mind ever fully in the world. When was the body ever fully in the world? Come to think of it, when was the world ever fully the world? (Though I'm not disagreeing that the task of philosophy is to find knowledge through alienation, I'm just querying the idea that alienation is unique to mind/humans/subjects whatever, and that it "happened" at some point in history.)

-Guy in the "sports jacket" has taken off his "sports jacket" to reveal a tan turtle neck.

-Negarestani breaks off from reading his paper, looks up at the audience, says, 'This is important', then carries on reading his paper.

-Negarestani says, 'What should we do to count as something?'

-Negarestani says, 'Mind has a history.'

-Negarestani says, 'True to the game' and some young guys behind me snigger and say, 'Yeah' in a fake deep voice.

-OK, hold on I think I have an idea of what he's saying - I think he is saying that to have a mind is to conceive of the mind as artificial or able to create artefacts, and that this conception of mind is historical, rather than natural.

-And this understanding sees mind as a project (historical) not an object (natural).

-Negarestani concludes and people start to rustle. He drinks from his glass of water and says, 'Part 2'. The rustling stops.

-Negarestani says, 'Knowledge should be suspicious of what it already knows.' 'To know is to preserve and mitigate ignorance.'

-Not many people taking notes. I'm wondering how you'd get through a lecture like this without having something else to do.

-Negarestani says, 'What knowledge needs to get rid of is the idea of uniqueness - the uniqueness of the world, the uniqueness of the mind.'

-The air conditioner comes on which is noisy but doesn't do much. The room is ever so slightly cooler, but perhaps a little damper.

-A bell goes off somewhere in the building and Negarestani looks up at the door and then continues.

-OK, another thing I'm getting - deep scepticism is central to this conception of knowledge/mind because you can only know the mind by looking at the world, and only understand the world by looking at the mind but actually by the time I wrote that I wasn't sure why.

-Negarestani says, 'Part three. Strategy one.'

-It's weird to conceive of a historical/historicised mind in such a detailed manner and then throw in the term, 'genuine freedom' as though it doesn't need explaining.

-Negarestani says something about dialectical materialism, fatalism and techno-singularity all maintaining an impoverished idea of history.

-Negarestani says something derogatory about Marxism and the guy in the "sport jacket"/turtle neck laughs and looks around.

-This impoverished version of history is unipathic, which I guess means it can only see one line from the past extending into the future.

-Nick Land (techno-capital-singularity) and Quentin Meillasoux (erm, dunno - some messianism maybe? Didn't hear him properly...) both make this mistake about what history is.

-Negarestani says, 'Real change is always a disruption or an eruption.'

-Negarestani says, 'Philosophy has a solution for this' but I didn't hear the problem.

-Negarestani says, 'A history that sees itself as one moment inevitably following another is not a history but a nature.'

-When listening to something I don't fully understand, I flip between finding it hard to follow and hearing it as a series of tautologies. Like, somehow is seems at once too complex to make sense, and too obvious to have meaning.

-Someone gets someone a glass of water, then someone offers someone a banana, then someone opens a window, then someone from the front row gets up and leaves the room.

-Someone asks a question and suddenly they are speaking about free jazz.

-Negarestani says, 'Rational compulsion', 'Rigorous psychosis.'

-And then like three questions later, someone else is asking about free jazz. Is this a thing in American philosophy lectures?

-A few questions later the second free jazz guy brings out a tape player and starts playing a weird slowed down sample, maybe recorded from the lecture itself. It seems kind of disrespectful considering we just sat through his jazz question.

-At the end of long lectures with extended Q & A sessions I feel a horror at the power and mutability of language.

-The last question is about Marxism and I'm worried that the questioner is going to be "that Marxist guy" and we're going to be here for ever.

-Some people have left, a few people are leaning over in their chairs, much of the audience have their coats and/or bags in their laps, one person has their face in their hands.

NY #7: Ethics and Aesthetics

I'm in New York with two other Open School East Associates to take part in a conference called Composing Differences at MOMA PS1.

Before we left for New York, we asked a few practitioners to share some material with us that we might be able to draw on for our presentation at the conference. Dexter Sinister sent us some bulletins from The Serving Library.

I just read Why Bother by Angie Keefer, it had a promising start about mistaking convergence for meaning, and then it mentioned Wittgenstein and I was hooked.

I love reading about Wittgenstein. I've read two biographies - one about his family (his brother was the most famous one armed pianist that ever lived), and one focusing on his infamous meeting with Karl Popper (where Wittgenstein apparently "brandished" a poker at the Viennese philosopher of science). I've also read Correction by Thomas Bernhard in which a Wittgenstein-esque philosopher builds a perfectly conical house for his sister before killing himself. And Wittgenstein's Mistress by David Markson in which an unnamed narrator experiences a literal version of the problem of solipsism.

As for his philosophy... I own both the Tractacus and Philosophical Investigations, but I bought them a long time ago before I had the necessary patience and understanding to fully engage with them. I get the general vibe of each book (they are almost totally contradictory as to what is the vital quality of language), but I don't know the text.

In Why Bother, Keefer describes the process of reading Wittgenstein and understanding why you would be interested in reading Wittgenstein. And she does an amazing job.

--

One section of the essay really struck me, and it's where she mentions A Lecture on Ethics, given by Wittgenstein in 1929.

Last year I listened to a lecture by Timothy Morton and he mentioned something about aesthetics being central to ethics. I liked the idea but I couldn't work out why. I googled the phrase and not much came up - or at least the stuff that came up didn't seem to be about the same idea that I understood when I heard Morton speaking.

It turns out that Wittgenstein understood me perfectly. Here is Angie Keefer explaining the main argument of A Lecture on Ethics.

'In the trivial sense, a word like ‘good’ accords with a pre-determined standard. i.e. Something is ‘good’ if it meets a quantifiable mark. Think of a good athlete or a good chess player or a good canoe. We know how to tell good from bad in each case because we have certain agreed upon metrics. That’s relative good. That’s the trivial sense. This trivial sense is, in turn, the basis of a metaphor we use to say something is good in the ethical sense. e.g. When I say, “Wittgenstein is a good person,” my meaning is conveyed because we understand ‘good’ in the relative sense and can draw on that sense of goodness as a metaphor for something that can’t be measured—an absolute good, a good “beyond” facts.

One way to detect whether a word is being used in the trivial or in the ethical sense is to try replacing it with other terms. If I say a canoe is good, and I mean the canoe is sea-worthy and will hold three people without

sinking, that is a defensible use of the word ‘good’. But if I say Wittgenstein is good, I can’t replace ‘good’ in the same way, with a standard measure. I have to rely on ethical arguments to substantiate my description. I am not dealing in facts. My meaning is ultimately indefensible.

In the first case—the canoe—I’ve made a logical proposition. It involves facts that can be vetted.

In the second case, I’ve issued an aesthetic statement. It can’t be verified.'

And then, Keefer carries on with Wittgenstein's words,

'Ethics, so far as it springs from the desire to say something about the ultimate meaning of life, the absolute good, the absolute valuable, can be no science.

What it says does not add to our knowledge in any sense.

But it is a document of a tendency in the human mind which I personally cannot help respecting deeply and I would not for my life ridicule it.'

Then, back to Keefer,

'The most meaningful (absolute) form eludes meaningful (relative) articulation, but the process of attempting

articulation is, itself, the practice of giving form to ethics. And that is what artists do.'

Before we left for New York, we asked a few practitioners to share some material with us that we might be able to draw on for our presentation at the conference. Dexter Sinister sent us some bulletins from The Serving Library.

I just read Why Bother by Angie Keefer, it had a promising start about mistaking convergence for meaning, and then it mentioned Wittgenstein and I was hooked.

I love reading about Wittgenstein. I've read two biographies - one about his family (his brother was the most famous one armed pianist that ever lived), and one focusing on his infamous meeting with Karl Popper (where Wittgenstein apparently "brandished" a poker at the Viennese philosopher of science). I've also read Correction by Thomas Bernhard in which a Wittgenstein-esque philosopher builds a perfectly conical house for his sister before killing himself. And Wittgenstein's Mistress by David Markson in which an unnamed narrator experiences a literal version of the problem of solipsism.

As for his philosophy... I own both the Tractacus and Philosophical Investigations, but I bought them a long time ago before I had the necessary patience and understanding to fully engage with them. I get the general vibe of each book (they are almost totally contradictory as to what is the vital quality of language), but I don't know the text.

In Why Bother, Keefer describes the process of reading Wittgenstein and understanding why you would be interested in reading Wittgenstein. And she does an amazing job.

--

One section of the essay really struck me, and it's where she mentions A Lecture on Ethics, given by Wittgenstein in 1929.

Last year I listened to a lecture by Timothy Morton and he mentioned something about aesthetics being central to ethics. I liked the idea but I couldn't work out why. I googled the phrase and not much came up - or at least the stuff that came up didn't seem to be about the same idea that I understood when I heard Morton speaking.

It turns out that Wittgenstein understood me perfectly. Here is Angie Keefer explaining the main argument of A Lecture on Ethics.

'In the trivial sense, a word like ‘good’ accords with a pre-determined standard. i.e. Something is ‘good’ if it meets a quantifiable mark. Think of a good athlete or a good chess player or a good canoe. We know how to tell good from bad in each case because we have certain agreed upon metrics. That’s relative good. That’s the trivial sense. This trivial sense is, in turn, the basis of a metaphor we use to say something is good in the ethical sense. e.g. When I say, “Wittgenstein is a good person,” my meaning is conveyed because we understand ‘good’ in the relative sense and can draw on that sense of goodness as a metaphor for something that can’t be measured—an absolute good, a good “beyond” facts.

One way to detect whether a word is being used in the trivial or in the ethical sense is to try replacing it with other terms. If I say a canoe is good, and I mean the canoe is sea-worthy and will hold three people without

sinking, that is a defensible use of the word ‘good’. But if I say Wittgenstein is good, I can’t replace ‘good’ in the same way, with a standard measure. I have to rely on ethical arguments to substantiate my description. I am not dealing in facts. My meaning is ultimately indefensible.

In the first case—the canoe—I’ve made a logical proposition. It involves facts that can be vetted.

In the second case, I’ve issued an aesthetic statement. It can’t be verified.'

And then, Keefer carries on with Wittgenstein's words,

'Ethics, so far as it springs from the desire to say something about the ultimate meaning of life, the absolute good, the absolute valuable, can be no science.

What it says does not add to our knowledge in any sense.

But it is a document of a tendency in the human mind which I personally cannot help respecting deeply and I would not for my life ridicule it.'

Then, back to Keefer,

'The most meaningful (absolute) form eludes meaningful (relative) articulation, but the process of attempting

articulation is, itself, the practice of giving form to ethics. And that is what artists do.'

NY #6: A House of Cards and A Naked Singularity

I'm staying with a friend in New York, and when we get back to her apartment at a reasonable time, we tend to watch a few episodes of House of Cards, a Netflix series starring Kevin Spacey as Frank Underwood, a ruthless and vengeful Democrat politician who will stop at nothing etc. etc.

I'd heard a while back that the show had been produced by Netflix using data that told them their subscribers' favourite writers, actors, storylines, moral themes, etc. The real story isn't quite as good, but it's got a similar vibe. David Fincher (Fight Club, Seven, The Social Network) had been recruited to write the first two episodes, and Kevin Spacey was committed to taking the starring role. Netflix outbid every other American TV company for the rights to air the series, and using analysis of the data they collect from their subscribers, were confident enough to commission two series straight off, without the need for a pilot. Kevin Spacey hadn't been a main character in a TV series since the late 80s, and David Fincher had never written for a major TV series, but Netflix know their data, and the first two series were immensely popular, with a third series on its way.

In the three or four episodes I've seen, Kevin Spacey has ruined about five careers, driven a guy to suicide, had an affair with a journalist and then killed that journalist by pushing her under a subway train. New characters appear constantly, seemingly just so they can be pulled into Spacey's giant tractor beam of shit to have their careers ruined/lives ended. It's relentless entertainment and it doesn't care how it entertains.

I haven't watched many episodes, but as far as I can tell, it has a very basic plot point upon which all this other action can be generated, 'Will Frank Underwood get away with it?'

Much like the mystery of who killed Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks, the answer to this question must stay just out of sight for the series to make sense and keep people watching.

--

I've been thinking about black holes. Gravitational singularity is the point inside a black hole where matter becomes infinitely dense and all rules of spacetime cease to make sense. It is beyond, and behind, the event horizon which is the point of no return - no light beyond the event horizon can reach an observer outside of the black hole.

I'd heard a while back that the show had been produced by Netflix using data that told them their subscribers' favourite writers, actors, storylines, moral themes, etc. The real story isn't quite as good, but it's got a similar vibe. David Fincher (Fight Club, Seven, The Social Network) had been recruited to write the first two episodes, and Kevin Spacey was committed to taking the starring role. Netflix outbid every other American TV company for the rights to air the series, and using analysis of the data they collect from their subscribers, were confident enough to commission two series straight off, without the need for a pilot. Kevin Spacey hadn't been a main character in a TV series since the late 80s, and David Fincher had never written for a major TV series, but Netflix know their data, and the first two series were immensely popular, with a third series on its way.

In the three or four episodes I've seen, Kevin Spacey has ruined about five careers, driven a guy to suicide, had an affair with a journalist and then killed that journalist by pushing her under a subway train. New characters appear constantly, seemingly just so they can be pulled into Spacey's giant tractor beam of shit to have their careers ruined/lives ended. It's relentless entertainment and it doesn't care how it entertains.

I haven't watched many episodes, but as far as I can tell, it has a very basic plot point upon which all this other action can be generated, 'Will Frank Underwood get away with it?'

Much like the mystery of who killed Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks, the answer to this question must stay just out of sight for the series to make sense and keep people watching.

--

I've been thinking about black holes. Gravitational singularity is the point inside a black hole where matter becomes infinitely dense and all rules of spacetime cease to make sense. It is beyond, and behind, the event horizon which is the point of no return - no light beyond the event horizon can reach an observer outside of the black hole.

The event horizon hides singularity from outside observers. Singularity has to be hidden from us, and this is as much a moral imperative as it is an observation of physics.

Basically, if we can see what's inside a black hole, then we might see something that renders unstable every practical implication of our current physics.

The Cosmic Censorship Hypothesis states that,

'If singularities can be observed from the rest of spacetime, causality may break down, and physics may lose its predictive power. The issue cannot be avoided, since according to the Penrose-Hawking singularity theorems, singularities are inevitable in physically reasonable situations. Still, in the absence of naked singularities, the universe is deterministic — it is possible to predict the entire evolution of the universe [...], knowing only its condition at a certain moment of time [...]. Failure of the cosmic censorship hypothesis leads to the failure of determinism'

The Wikipedia article goes on to explain that the hypothesis is not formal, i.e., there's no maths involved yet, it's just that most physicists feel that they shouldn't ever be allowed to observe a singularity.

This fearsome possibility, a black hole without an event horizon, is called a naked singularity. A naked singularity would make it possible to observe the collapse of matter to an infinite density, ruining the predictive powers of physics forever.

--

Before I came to New York I read (devoured might be a better word) the book A Naked Singularity by Sergio de la Pava.

The book was self published by de la Pava in 2008, and then after an enthusiastic response, it was taken up by Chicago University Press and eventually the publishers of Stieg Larsson in 2013. It won the PEN prize for debut fiction and de la Pava has been hailed as the new Dickens/Joyce/Pynchon/David Foster Wallace.

I loved reading the book, but I was cynical of my own enjoyment. It was like it had been focus grouped to appeal to me circa two years ago. For a while, all the books I read were by Giant American Post-modernists - Pynchon, Don DeLillo and particularly David Foster Wallace. I've read everything DFW wrote that has been published, including a not very good essay on hip hop, and a pathetic posthumous collection of essays and fragments that reminded me of those albums 2Pac is still releasing.

The book has everything that I already enjoy reading - a flowing, first person narrative, absurdist humour with magical realist tendencies, essayistic digressions into art, philosophy and pop culture, and a long story about a man shitting his pants.

The book is mostly about the main character, Casi - a public defender working in Manhattan and living in Brooklyn - being a human in the world, but the storyline presented by the book is about Casi taking part in a scheme to rob some drug dealers. The lacuna at the heart of the story is firstly whether or not Casi will go through with the robbery, and then after he does, whether or not he'll get caught.

Like all the best art, you don't find out the answer to that last question. The possibilities of the book spill out infinitely beyond the last page, leaving the reader distraught at not knowing the thing they can't really want to know.

NY #5: Beating the Sky With his Fists

Steve Reinke has an amazing video at the Whitney Biennial called Rib Gets In the Way (Final Thoughts, Series Three). It has several wonderful sequences in its 53 minutes - one long section at the end is an animated version of Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra with drawings made by primary school children. It also contains excerpts from a video of Jacques Lacan speaking at Louvain University in 1972.

The excerpts of the lecture (roughly the first half of this youtube video) are great. Lacan is in full command of his performance. At one point he talks about death. Actually, he kind of shouts about it.

Then, halfway through the lecture, a student comes on stage and performs a muted protest, pouring water over Lacan's notes and making a confused statement about revolution and love.

The student is beautiful, with pouting lips and lank teenage hair. His body is oversized like a teenager, and he is angry at Lacan ('People like you'). Eventually he is led away and Lacan continues. But before that, Lacan takes some time to deals with his interruption, allowing him to speak and then addressing his concerns.

It's an impressive performance, but it's sad to watch. The fawning audience are desperate to laugh at Lacan's dismissal of the man-boy's immature politics. The adolescent ideas of utopia and revolution are dealt with like mistakes or embarrassing confessions, rather than actual desires - whether political or libidinal.

'What is really incredible is that he imagined, that by beating the sky with his fists, this alienation - which is exactly what he was telling you about - is a sort of call. For what? For more truth?'

The excerpts of the lecture (roughly the first half of this youtube video) are great. Lacan is in full command of his performance. At one point he talks about death. Actually, he kind of shouts about it.

'Death belongs to the realm of faith. You're right to believe you will die. It sustains you. If you didn't believe it could you bear the life you have? If we couldn't totally rely on the certainty that it will end, how could you bear this? Nevertheless, it is only an act of faith. And the worst thing about it is that you're not sure.'

--

Then, halfway through the lecture, a student comes on stage and performs a muted protest, pouring water over Lacan's notes and making a confused statement about revolution and love.

The student is beautiful, with pouting lips and lank teenage hair. His body is oversized like a teenager, and he is angry at Lacan ('People like you'). Eventually he is led away and Lacan continues. But before that, Lacan takes some time to deals with his interruption, allowing him to speak and then addressing his concerns.

It's an impressive performance, but it's sad to watch. The fawning audience are desperate to laugh at Lacan's dismissal of the man-boy's immature politics. The adolescent ideas of utopia and revolution are dealt with like mistakes or embarrassing confessions, rather than actual desires - whether political or libidinal.

'What is really incredible is that he imagined, that by beating the sky with his fists, this alienation - which is exactly what he was telling you about - is a sort of call. For what? For more truth?'

NY #4: Acceptable Blockages on Tour

Since about 2010 I've taken photos of improvised arrangements of street furniture that I call Acceptable Blockages. I think of the areas they delineate as modern magic circles or sacred spaces. I guess they also say a lot about how we communicate with each other in cities, and how communication works as much through habituation and assumption as it does through meaning and understanding.

I did a lecture about it in 2011 which you can read here.

I still take plenty of photos. I have a collection of around 200.

In New York, a bit like American English, the vernacular is a bit different from the UK, but not so much that you don't recognise the meaning of the language.

I did a lecture about it in 2011 which you can read here.

I still take plenty of photos. I have a collection of around 200.

In New York, a bit like American English, the vernacular is a bit different from the UK, but not so much that you don't recognise the meaning of the language.

NY #3: Ambient Notes #12 (Franz Erhard Walther at The Drawing Center)

-The website says the talk starts at 7pm. The receptionist says it starts at 6:30 so we go downstairs where we sit and wait for 30 minutes.

-A woman dressed all in black stands in front of the waiting audience and takes a photo on her iPhone.

-A pretty girl with half a shaved head is sitting a few rows in front. She looks familiar.

-I go to the toilet and pass the thick yellow piss of a person whose hangover is still in control of his bodily functions.

-I'm looking at the pretty, shaven headed girl and as two people arrive at the talk behind me, she turns around, catches my eye and waves. I'm flustered and look around to see if she is waving at the people behind me. When I turn back, she's stopped waving and is facing forward again. I still can't work out if I know her, and if I do then I've just completely blanked her.

-The chairs for the audience are plastic and thick-legged and kind of orthopaedic in vibe.

-This talk is part of ART2, a month long project in New York organised by the French Embassy. The logo for the project is apparently three apples (as in the big apple) and three Eiffel towers (as in Paris).

-Just before they start the talk, they turn all the lights off and it becomes very hard to see my notepad.

-The director of the Drawing Center does an intro where he basically admits that the talk has nothing to do with the programme of the gallery but they are doing it anyway, I guess the French Embassy can pay pretty good rates. He uses the term 'Interesting canopy'.

-The French curator or organiser or whatever does an intro but doesn't stand up. I'm at the back and I can't see where she is sitting. I'm confused about where her voice might be coming from.

-Weirdly (for a curator) she is talking quite directly about her research interests in the first person ('I was interested'), rather than in the passive ('It was interesting'), which is ironic since I can't identify where or who she is.

-The artist is a big German man, with a wide face and huge, meaty fists.

-The curator is still going on her intro. She is basically reading out an essay to or at the artist who nods and occasionally confirms details.

-Neither the curator nor the artist are miked up, and when the curator finally asks the artist a question it's very hard to hear him.

-The artist refers to his own work as revolutionary.

-'EXIT' signs in the U.S. (as in fire exit signs) are red (as opposed to green in the U.K.). The 'EXIT' sign is right behind the artist and makes the whole thing look a bit seedy.

-To be honest I'm only half listening to the lecture because to listen properly requires serious concentration with almost lip-reading type focus on the mouth of the artist as he speaks. When I can hear what they're saying it seems like they are having a hard time making a conversation about the material under discussion.

-Occasionally latecomers arrive from a corridor at the back of the room. They are all, without exception, formally dressed, middle aged French people whose shoes click on the polished concrete floor as they enter.

-I think I don't know the girl with the shaved head. I think she just reminds me of a friend's ex-girlfriend. They moved to Japan and she dumped him for another guy and then moved to Australia and got married.

-Since I got to the U.S. I've been having dreams where I pick a gravelly, metallic wax out of my ears. In the dreams, when the wax finally comes out it is a moment of release, almost a kind of jouissance, and when I awake I am disappointed it wasn't real.

-On screen: a drawing with the words, 'WORK IS ACTION', 'SPACES', 'PROCESSES' and the word 'OUT' upside down.

-The ear wax dreams remind me of dreams I used to have where I could suck my own dick. They recurred a lot, to the point where the dreams took the form of me dreaming that I remembered dreams of me sucking my own dick and was surprised to find that I was able to manage it in real life (in the dream).

-I feel radically under dressed. The person doing the AV is in a dress and heels.

-The artist tells a story about Marcel Duchamp phoning him up and asking to meet him, but the artist was too busy and then Marcel Duchamp died. 'Too bad' says the artist.

-On screen: an unexplained image of a building that the artist may have designed?

-The curator unexpectedly opens up to questions from the audience. The first questions are things like, 'What is on screen?' 'What is that building?' and 'Is this something you did?'

-It turns out that the artist hates this building he designed, 'They ruined it, take the image away now.'

-Someone in the front row leans forward and I see the curator's face for the first time.

-Someone asks a question in which they keep addressing the artist by his first name and then the question just turns into a story about how the questioner went to see one of the artist's exhibitions in 1989 and thought it was great.

-An ex-girlfriend of mine once pulled a long hollow cone of wax from my ear with tweezers, like 2cm long, all in one huge piece. I can remember her saying, 'Wow' and it felt amazing and at the time we were very much in love.

-I don't have the dreams where I can suck my own dick any more. As I remember, I think I only had them when I was in long term relationship.

-A woman dressed all in black stands in front of the waiting audience and takes a photo on her iPhone.

-A pretty girl with half a shaved head is sitting a few rows in front. She looks familiar.

-I go to the toilet and pass the thick yellow piss of a person whose hangover is still in control of his bodily functions.

-I'm looking at the pretty, shaven headed girl and as two people arrive at the talk behind me, she turns around, catches my eye and waves. I'm flustered and look around to see if she is waving at the people behind me. When I turn back, she's stopped waving and is facing forward again. I still can't work out if I know her, and if I do then I've just completely blanked her.

-The chairs for the audience are plastic and thick-legged and kind of orthopaedic in vibe.

-This talk is part of ART2, a month long project in New York organised by the French Embassy. The logo for the project is apparently three apples (as in the big apple) and three Eiffel towers (as in Paris).

-Just before they start the talk, they turn all the lights off and it becomes very hard to see my notepad.

-The director of the Drawing Center does an intro where he basically admits that the talk has nothing to do with the programme of the gallery but they are doing it anyway, I guess the French Embassy can pay pretty good rates. He uses the term 'Interesting canopy'.

-The French curator or organiser or whatever does an intro but doesn't stand up. I'm at the back and I can't see where she is sitting. I'm confused about where her voice might be coming from.

-Weirdly (for a curator) she is talking quite directly about her research interests in the first person ('I was interested'), rather than in the passive ('It was interesting'), which is ironic since I can't identify where or who she is.

-The artist is a big German man, with a wide face and huge, meaty fists.

-The curator is still going on her intro. She is basically reading out an essay to or at the artist who nods and occasionally confirms details.

-Neither the curator nor the artist are miked up, and when the curator finally asks the artist a question it's very hard to hear him.

-The artist refers to his own work as revolutionary.

-'EXIT' signs in the U.S. (as in fire exit signs) are red (as opposed to green in the U.K.). The 'EXIT' sign is right behind the artist and makes the whole thing look a bit seedy.

-To be honest I'm only half listening to the lecture because to listen properly requires serious concentration with almost lip-reading type focus on the mouth of the artist as he speaks. When I can hear what they're saying it seems like they are having a hard time making a conversation about the material under discussion.

-Occasionally latecomers arrive from a corridor at the back of the room. They are all, without exception, formally dressed, middle aged French people whose shoes click on the polished concrete floor as they enter.

-I think I don't know the girl with the shaved head. I think she just reminds me of a friend's ex-girlfriend. They moved to Japan and she dumped him for another guy and then moved to Australia and got married.

-Since I got to the U.S. I've been having dreams where I pick a gravelly, metallic wax out of my ears. In the dreams, when the wax finally comes out it is a moment of release, almost a kind of jouissance, and when I awake I am disappointed it wasn't real.

-On screen: a drawing with the words, 'WORK IS ACTION', 'SPACES', 'PROCESSES' and the word 'OUT' upside down.

-The ear wax dreams remind me of dreams I used to have where I could suck my own dick. They recurred a lot, to the point where the dreams took the form of me dreaming that I remembered dreams of me sucking my own dick and was surprised to find that I was able to manage it in real life (in the dream).

-I feel radically under dressed. The person doing the AV is in a dress and heels.

-The artist tells a story about Marcel Duchamp phoning him up and asking to meet him, but the artist was too busy and then Marcel Duchamp died. 'Too bad' says the artist.

-On screen: an unexplained image of a building that the artist may have designed?

-The curator unexpectedly opens up to questions from the audience. The first questions are things like, 'What is on screen?' 'What is that building?' and 'Is this something you did?'

-It turns out that the artist hates this building he designed, 'They ruined it, take the image away now.'

-Someone in the front row leans forward and I see the curator's face for the first time.

-Someone asks a question in which they keep addressing the artist by his first name and then the question just turns into a story about how the questioner went to see one of the artist's exhibitions in 1989 and thought it was great.

-An ex-girlfriend of mine once pulled a long hollow cone of wax from my ear with tweezers, like 2cm long, all in one huge piece. I can remember her saying, 'Wow' and it felt amazing and at the time we were very much in love.

-I don't have the dreams where I can suck my own dick any more. As I remember, I think I only had them when I was in long term relationship.

NY #2: Interference Archive/Effective Action Against Violent Attacks on Business

On Thursday we went to the Interference Archive in Brooklyn. It's a collection of cultural material produced by social movements.

We met Josh MacPhee - one of the 'core collective' who run the archive - and he told us how it started (from his personal collection, and the collection of Dara Greenwald), how they run it (on a tiny budget, with volunteers who are mainly archivists in other, bigger institutions and are dissatisfied with the way those larger archives are run), and why it was so cold in there (the heating got turned off last week when the weather turned warm, and now it's snowing again).

That's the top of Jon's hat and lots of boxes.

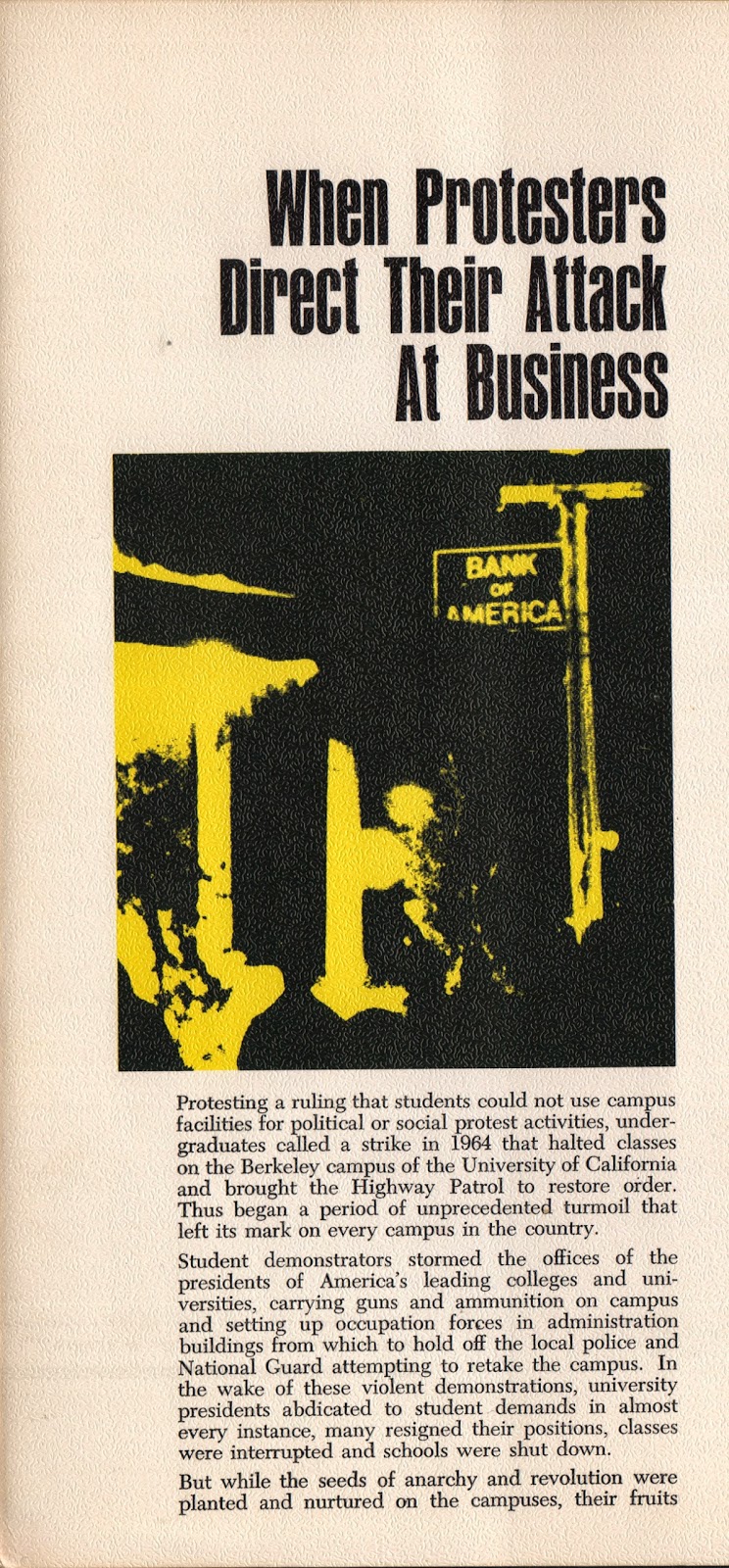

Josh happened to mention a pamphlet they'd been given called Effective Action against violent attacks on business, produced by the Californian State Chamber of Commerce after students from University of California at Santa Barbara burned down a branch of Bank of America in Isla Vista in 1970.

It's a really fascinating piece of history. As Josh said, propaganda used to reinforce the status quo rarely wants to be seen as propaganda, so it's good that someone thought to pass it on to the archive.

I've scanned the pamphlet below, and then below that there are some transcribed quotes from the main body of the text.

There's a couple of weird things about the pamphlet. One is that all the inset quotes in a larger typeface are from American figures of the left in support of the revolution.

'If America Doesn't come around we're going to burn America down.'

'As long as an act is revolutionary it cannot be regarded as a crime.'

'The students who burned the Bank of America in Santa Barbara may have done more for the environment than all the teach-ins put together.'

I guess they were meant to scare people, but it means that the dominant voices in the pamphlet are those of the revolutionary left, which is probably something of a misjudgement in propaganda terms.

The other thing is that although it was produced as a resource for businesses wanting to prevent attacks or demonstrations, the language used in the pamphlet is heavily influenced by the socialist politics that they describe. For instance, the word terrorism doesn't appear once in the whole pamphlet. The student groups are described as revolutionaries or movements. And though the pamphlet makes jokes at the expense of the groups ('There seems to be a revolutionary group for every three letter combination of the alphabet'), it also takes their aims and ideals seriously. It's hard to remember there was a time when socialist revolution was seen as a real possibility/threat, by the left or the right.

We met Josh MacPhee - one of the 'core collective' who run the archive - and he told us how it started (from his personal collection, and the collection of Dara Greenwald), how they run it (on a tiny budget, with volunteers who are mainly archivists in other, bigger institutions and are dissatisfied with the way those larger archives are run), and why it was so cold in there (the heating got turned off last week when the weather turned warm, and now it's snowing again).

That's the top of Jon's hat and lots of boxes.

Josh happened to mention a pamphlet they'd been given called Effective Action against violent attacks on business, produced by the Californian State Chamber of Commerce after students from University of California at Santa Barbara burned down a branch of Bank of America in Isla Vista in 1970.

It's a really fascinating piece of history. As Josh said, propaganda used to reinforce the status quo rarely wants to be seen as propaganda, so it's good that someone thought to pass it on to the archive.

I've scanned the pamphlet below, and then below that there are some transcribed quotes from the main body of the text.

There's a couple of weird things about the pamphlet. One is that all the inset quotes in a larger typeface are from American figures of the left in support of the revolution.

'If America Doesn't come around we're going to burn America down.'

'As long as an act is revolutionary it cannot be regarded as a crime.'

'The students who burned the Bank of America in Santa Barbara may have done more for the environment than all the teach-ins put together.'

I guess they were meant to scare people, but it means that the dominant voices in the pamphlet are those of the revolutionary left, which is probably something of a misjudgement in propaganda terms.

The other thing is that although it was produced as a resource for businesses wanting to prevent attacks or demonstrations, the language used in the pamphlet is heavily influenced by the socialist politics that they describe. For instance, the word terrorism doesn't appear once in the whole pamphlet. The student groups are described as revolutionaries or movements. And though the pamphlet makes jokes at the expense of the groups ('There seems to be a revolutionary group for every three letter combination of the alphabet'), it also takes their aims and ideals seriously. It's hard to remember there was a time when socialist revolution was seen as a real possibility/threat, by the left or the right.

Quotes:

'Understandably, a businessman is absorbed in his immediate interests. However there are times when he will be faced with the hard decision of whether or not to temporarily and voluntarily modify his traditional standard of profit and loss in the light of more overriding, long-range considerations of national interest.'

'The businessman has every right to combat the organized campaigns of radical elements. At the same time he should ask himself some pertinent questions regarding his relationship with his fellow man. [...] Is there a tendency to take advantaged of the less privileged when selling to them the necessities of life such as food, shelter, clothing and health care? [...] In short, is business doing all it can within its capabilities, to serve the needs of society as well as the needs of business?'

'Our society is held together by a mutual, though often unstated, agreement to work together through a system of law, order, justice and human relationships, even to the point of forsaking self-interest at times.'

'Lasting solutions needed to turn the energies of destruction into meaningful programs for progress will; have to be explored continuously by all concerned business leaders. The task is one of changing attitudes. It must begin with the attitudes of business itself.'

'Even the new womens' rights movements and the Gay Liberation Front (homosexuals) have added their voices to the battle cry.'

'The goal should be to support our country, recognize its faults and work together to improve it. We must convince our young people that change can be made, working within the framework of our present free society. We must show them what participatory democracy is all about.'

NY #1: A Poem for The Frick Collection

In the Frick Collection there are people here who don't know why they're here

like us.

There's a promotional film that reflects the American attitude to patronage

with such a savage lack of irony that you might take it for satire

but you don't.

Children look bored.

Jon says,

looking at some ridiculous French writing desk from the 18th c.,

that you can understand why all those aristocrats got beheaded.

The audio guide keeps telling me that the painting I'm looking at

is the most beautiful example

of whatever kind of painting it is in the world

which seems unlikely.

But you can't fuck with the El Grecos, or the Goyas,

and a lot of the early Renaissance painting is pretty great too.

like us.

There's a promotional film that reflects the American attitude to patronage

with such a savage lack of irony that you might take it for satire

but you don't.

Children look bored.

Jon says,

looking at some ridiculous French writing desk from the 18th c.,

that you can understand why all those aristocrats got beheaded.

The audio guide keeps telling me that the painting I'm looking at

is the most beautiful example

of whatever kind of painting it is in the world

which seems unlikely.

But you can't fuck with the El Grecos, or the Goyas,

and a lot of the early Renaissance painting is pretty great too.

Tops Off for Jordan Wolfson

There's this thing in Glasgow where, at parties or occasionally in clubs, the male students on the Fine Art MFA at the School of Art take their tops off. Someone shouts, 'TOPS OFF!' and then they take their tops off and dance.

Actually, according to Liz who I stayed with while I was in Glasgow, the pronunciation is more like, 'TAPS AFF!'

I know this because on Thursday night, before we went to the Art School for the opening party of the 2014 Glasgow International Festival, we went to Liz's studio so I could drop off my luggage and drink some wine. At one point, as Liz and some other people smoked in the kitchen, I stood next to a fake leather sofa speaking to Kev and someone called Stef (who was beautiful with a big nose which is like one of the features I find really attractive and I was wondering whether I could maybe try and come on to her later but I never did because she disappeared at some point in the evening and so instead I just drank as much gin as I could manage and flirted with someone I know from London until I realised she had a boyfriend.). They were trading funny stories about Venice and Kev got over excited and spilled red wine all over his shirt and the fake leather sofa.

He jumped up from the sofa and we followed him into the kitchen to help clean the wine off, but before we could find a cloth, he had removed his shirt, exposing his back and a small amount of arse, to the amusement of everyone but particularly to Liz and her friends Erin and Amy who kept shouting, 'TAPS AFF! TAPS AFF!!' as they smoked their cigarettes and everyone laughed and Kev demanded to know if anyone had a hair dryer.

--

I'd heard about Jordan Wolfson's work via Lucy at Open School. She had sent round a Frieze blog about his video piece, Raspberry Poser at Chisenhale Gallery. In the article, Jonathan P. Watts writes about the experience of attending a memorial service for what would have been Derek Jarman's 72nd birthday, and then the next day, visiting Wolfson's Chisenhale show.

The blog makes a powerful point about Wolfson (who is straight), appropriating the HIV virus as a found object for aesthetic purposes (literally - in the video 3D animated HIV cells bounce up and down in New York streets and luxury interiors),

'If Wolfson has anxieties about his own private wealth, his own tendency for posturing, his own megalomaniac neuroses, the legacy of the AIDS crisis should not be a vehicle for this.'

Lucy made it clear that she fully agreed with the writer's sentiment. The word trespassing came up a lot in the discussions we had. I hadn't seen the work, I said, but I wondered if respecting limits to who should access certain histories might play into a wider, less politically admirable notion that certain histories should remain ghettos.

I missed the Chisenhale show, but I finally saw Wolfson's work at McLellan Galleries as part of Glasgow International. Raspberry Poser was there, alongside previous works dating back to 2004.

Some of the show left me cold - I'm not so interested in The Digital as subject matter and various works of 3D animation transferred to 16mm seemed to inhabit the tendency of some artists to see contemporary technology as necessarily interesting.

But a few films stood out for me because of the discomfort and pleasure I felt while watching them. Particularly Raspberry Poser (2012) and Animation, Masks (2011).

They stood out because the voice that came through seemed to speak from the end of completed journey, a project to acquire total inauthenticity, a radicalised bourgeois nihilism. Or maybe just an honesty and a tiredness.

Animation, Masks contained moments of gleefully misogynistic eroticism (or at least, it presented scripted moments of gleefully misogynistic eroticism). A pillow talk conversation, voiced by an animated stereotype of a Jew ended with a male voice (Wolfson?) forcing a woman to repeat the phrase 'I like it when you tell me what to do', over and over again. The most appropriate public response would be an awkward laugh. But privately I was turned on by the conversation between the man and the woman. Or maybe it would be more precise to say I was turned on by my understanding of the transgressive nature of presenting such a conversation in an artwork. I didn't "agree" with the film, but then what would that even mean? Who would I be agreeing with? It was so constructed and yet it repelled any reading of its author's intention. A shrug of the shoulders with an erection.

--

In the cab to an exhibition at the Botanical Gardens we spoke about Wolfson's show. John Ryan said that Wolfson had given a lecture at Glasgow School of Art where he'd said something like, 'I'm one of the the best artists in the world right now, and that's because I practise transcendental meditation'.

I said that I'd tried meditating a few times. The first time I couldn't think of a mantra and accidentally got the words 'Transcendental meditation' stuck in my head. I said that when I cycled I sometimes thought the phrase, 'Strong, powerful movements of the leg'. The second time I tried to meditate, I got that stuck in my head.

--

That evening, after drinking all afternoon, we went to a party at the Barrowlands in the East End of Glasgow. We danced a lot, a pissed art crowd of people who'd been at the festival for the weekend.

Occasionally I shouted, 'TOPS OFF!' at Liz, and Liz shouted 'TOPS OFF!' back at me. We were surrounded by her friends from the MFA who I didn't really know, but I still shouted it. It seemed funny at the time. Eventually one of the boys did take their tops off. And then, after some initial apprehension in the group, they all started taking their tops off and there was a mass of shirtless male students in the centre of the dance floor, bouncing around to the music. Women were occasionally pulled into the group, expressing a mixture of horror and humour on their faces. It looked funny but not fun.

I kept my top on and carried on dancing, occasionally turning to marvel at the fleshy mass spinning in front of me. They stank. I wasn't sure whether it was just because they no longer had shirts to soak up the sweat, or whether the adrenaline was releasing some kind of homo-social musk.

At the climactic moment of the evening (or the nadir, depending on how you were feeling), the DJ played Love is in the Air by John Paul Young and people danced hard like at the end of a wedding. There were a lot of hands in the air and pointing of fingers and some of them were mine.

The music finished and the lights came up and I stood watching as a mass of drunken, dishevelled people milled around trying to work out where the party was. I felt turned on then too, but not by anyone in particular, just by the sweat on everyone's bodies that refused to smell like anything else.